- Home

- Ijeoma Oluo

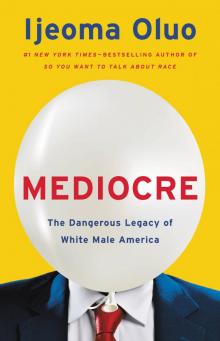

Mediocre

Mediocre Read online

Copyright © 2020 by Ijeoma Oluo

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover images © ferrantraite via Getty Images; © ArpornSeemaroj / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright © 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Seal Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.sealpress.com

@sealpress

First Edition: December 2020

Published by Seal Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Seal Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020944625

ISBNs: 978-1-58005-951-0 (hardcover), 978-1-58005-950-3 (ebook)

E3-20201029-JV-NF-ORI

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Works According to Design

1. Cowboys and Patriots:

How the West Was Won

2. For Your Benefit, in Our Image:

The Centering of White Men in Social Justice Movements

3. The Ivy League and the Tax Eaters:

White Men’s Assault on Higher Education

4. We Have Far Too Many Negroes:

White America’s Bitter Dependency on People of Color

5. Fire the Women:

The Convenient Use and Abuse of Women in the Workplace

6. Socialists and Quota Queens:

When Women of Color Challenge the Political Status Quo

7. Go Fucking Play:

Football and the Fear of Black Men

Conclusion:

Can White Manhood Be More Than This?

Acknowledgments

Discover More

Notes

About the Author

Also By Ijeoma Oluo

Advance Praise For Mediocre

This book is dedicated to Black womxn: You are

more important than white supremacy.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

INTRODUCTION

Works According to Design

I was at an idyllic women’s writing retreat. I spent my days in a charming cabin surrounded by trees, kept warm by a little woodstove. As I looked out the window to the giant evergreens surrounding my cabin, I was supposed to feel the spark of inspiration. But I wasn’t feeling inspired yet. This setting was quite a change for someone like me: a single mom of two boys used to writing over the din of crashes and bangs and shouts and her own attention deficit disorder. I had adapted to being creative even with a teenage boy regularly interrupting to tell me that he needed more snacks and, yes, was still incapable of finding them himself.

But this writing retreat was designed to get women away from the cries of “Mom!” or “Honey?” that so often compete for our brain space. We were supposed to be honoring our creativity by giving it the time and space it deserved. No children, no men, no internet, no television.

So we worked each day in solitude, and then every evening, at around six p.m., all five of us writers would leave our individual cabins and gather for dinner in the main farmhouse. Over a lovingly prepared meal made with vegetables freshly pulled from the farmhouse garden, we would discuss our writing projects, asking each other questions and offering support and encouragement. We talked about the work we were doing: the books we were writing, the plays we wanted to write. We floated ideas, asked for advice about agents and editors. We laughed and drank wine.

But more than anything, we talked about men. Not our partners or friends or brothers—we talked about shitty dudes. And even though we came from diverse racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds, we all had plenty of dudes to talk about. We talked about the white men in publishing who were constantly devaluing our work. We talked about the male writers who would grab your ass at book fairs or offer to give you feedback on your work and then try to sleep with you. We talked about how much time we had spent writing about shitty white dudes. Because if we weren’t writing about the president, we were writing about how men without uteruses should not control our reproductive choices, or about how rapists should actually go to jail for rape—even if they were gifted athletes.

Every evening, we would come together and talk about how we were trying to write and live in a world run by men who seemed pretty determined to stop us from having a voice, from experiencing success—from having our own free and independent lives. And I know this isn’t a problem that’s particular to the writing industry. I’ve participated in similar conversations when I worked in advertising and when I worked in tech. These are conversations, I’m sure, that women find themselves having in just about any job they have, in every school they attend, and in every community where they live. There is an abundance of bad guys to be found just about everywhere, and we can’t seem to stop talking about them.

“Works according to design.”

This is a comment that I and many of my fellow racial justice commentators have made when truly horrible things happen, just as they were intended to. A police officer shot an unarmed Black man, and a grand jury decided that the officer didn’t even need to face trial? Works according to design. A kid of color selling weed will be sentenced to years in prison while a wealthy white man receives house arrest for his second DUI? Works according to design.

Although the phrase may seem alarmingly coldhearted, it is our way of reminding ourselves that the greatest evil we face is not ignorant individuals but our oppressive systems. It is a reminder that the deaths of Trayvon Martin and Sandra Bland are not isolated cases. It is a reminder to refuse to let our shock and outrage distract us into thinking that these incidents do not all stem from the same root source, which must be dismantled. That source is white male supremacy.

White men lead our ineffective government with almost guaranteed reelection. They lead our corrupt and violent criminal-justice system with little risk of facing justice themselves. And they run our increasingly polarized and misinforming media, winning awards for perpetrating the idea that things run best when white men are in charge. This is not a stroke of white male luck; this is how our white male supremacist systems have been designed to work.

And when I say “white supremacy,” I’m not just talking about Klan members and neo-Nazis. Blatant racial terrorists—while deadly and horrifying—have never been the primary threat to people of color in America. It’s more insidious than that. I am talking about the ways our schoolrooms, politics, popular culture, boardrooms, and more all prioritize the white race over other races. Ours is a society where white culture is normalized and universalized, while cultures of color are demonized, exotified, or erased.

The average Black household in the United States has one-thirteenth of the net financial worth of the average white household; the average Hispanic household has one-eleventh. One-third of Black men in America are expected t

o be imprisoned in the course of their lives. As stark as these numbers seem, we people of color—especially women of color—live with these realities every day. Our entire society is built to ensure that white men hoard power. And it’s important to remember that the women and people of color most violently harmed by these systems are those who are also queer, transgender, or disabled.

The “male supremacy” in white male supremacy has been in place in white culture since before white people thought of themselves as white. For centuries, women were not allowed to own property, to attend university, to vote. Whatever degree of freedom women and girls had in their public and private lives was determined by men.

Women still spend a large portion of their lives battling men for their basic dignity and safety. They face the persistence of the gender wage gap, the fact that one in five women is a victim of sexual assault, and the ongoing debate about whether male abusers should keep their jobs and even their status.

These injustices are not passed down by God; they are not produced by any entity greater than ourselves. These oppressive systems were built by people—with our votes, our money, our hiring decisions—and they can be unmade by people.

So, at this beautiful dinner table in a farmhouse in the woods, as we continued talking about these white men and their unchecked anger, fear, and irresponsibility—this phrase kept popping into my head: works according to design.

I thought about the white men who talked over me in meetings. I thought about the white male lead in a movie who sits in his cubicle and laments his lot, bemoaning that he was supposed to be so much more. I thought about the white men wearing swastikas in Charlottesville, angry about their own failures and shouting about the people they blamed for them.

I thought of every think piece published since the 2016 election trying to explain the new angry white man. He was disillusioned, he was afraid. He was dissatisfied with his job and his elected representatives. He felt forgotten and left behind. Our modern, pluralist world’s focus on diversity had harmed white men in some real way, leading to this age of white male anger. At least, that is what the pundits said.

And here we were, a group of accomplished women talking about these white men as if they were a problem that had recently fallen upon us from the sky, instead of the predictable product of centuries of cultural, political, and economic conditioning.

And suddenly, my anxiety of the last few days faded, because I knew that I was going to write this book.

“Lord, give me the confidence of a mediocre white man.”

When writer Sarah Hagi said those words in 2015, they launched a thousand memes, T-shirts, and coffee mugs. The phrase has now become a regular part of the lexicon of many women and people of color—especially those active on social media. The sentence struck a chord with so many of us because while we seemed to have to be better than everyone else to just get by, white men seemed to be encouraged in—and rewarded for—their mediocrity.

White male mediocrity seems to impact every aspect of our lives, and yet it only seems to be people who aren’t white men who recognize the imbalance.

I am not arguing that every white man is mediocre. I do not believe that any race or gender is predisposed to mediocrity. What I’m saying is that white male mediocrity is a baseline, the dominant narrative, and that everything in our society is centered around preserving white male power regardless of white male skill or talent. I also know that many white men accomplish great things. But I will argue that we condition white men to believe not only that the best they can hope to accomplish in life is a feeling of superiority over women and people of color, but also that their superiority should be automatically granted them simply because they are white men. The rewarding of white male mediocrity not only limits the drive and imagination of white men; it also requires forced limitations on the success of women and people of color in order to deliver on the promised white male supremacy. White male mediocrity harms us all.

When I talk about mediocrity, I am not talking about something bland and harmless. I’m talking about a cultural complacency with systems that are horrifically oppressive. I’m talking about a dedication to ignorance and hatred that leaves people dead, for no other reason than the fact that white men have been conditioned to believe that ignorance and hatred are their birthrights and that the effort of enlightenment and connection is an injustice they shouldn’t have to face.

When I talk about mediocrity, I talk about how we somehow agreed that wealthy white men are the best group to bring the rest of us prosperity, when their wealth was stolen from our labor.

When I talk about mediocrity, I am talking about how aggression equals leadership and arrogance equals strength—even if those white male traits harm the men themselves and the kingdom they hope to rule.

When I talk about mediocrity, I talk about success that is measured only by how much better white men are faring than people who aren’t white men.

When I talk about mediocrity, I am talking about the ways in which we can’t imagine an America where women aren’t sexually harassed at work, where our young people of color aren’t funneled into underresourced schools—all because it would challenge the idea of the white male as the center of our country. This is not a benign mediocrity; it is brutal. It is a mediocrity that maintains a violent, sexist, racist status quo that robs our most promising of true greatness.

By defining greatness as a white man’s birthright, we immediately divorce it from real, quantifiable greatness—greatness that benefits, greatness that creates. White men have assumed inborn greatness, and they are taught to believe that they alone have seemingly infinite potential for greatness. Our culture has shaped the expectation of greatness exclusively around white men by erasing the achievements of women and people of color from our histories, by excluding women and people of color as heroes in our films and books, by ensuring that the qualified applicant pool is restricted to white male social networks.

But the expectation of accomplishment is not an accomplishment in and of itself. By making whiteness and maleness their own reward, we disincentivize white men from working to earn their privileged status. If you are constantly assumed to be great just for being white and male, why would you struggle to make a real contribution? Why take a risk or make a determined effort that might fail when you can be rewarded for keeping your head down? Societal incentives are toward mediocrity.

Most women and people of color have to claw their way to any chance at success or power, have to work twice as hard as white men and prove themselves to be exceptional talents before we begin to entertain discussions of truly equal representation in our workplaces or government. Somehow, we don’t think white men should be required to shoulder any of the same burden for growth and struggle the rest of us are expected to work through in order to accomplish anything worthwhile.

How often have you heard the argument that we have to slowly implement gender and racial equality in order to not “shock” society? Who is the “society” that people are talking about? I can guarantee that women would be able to handle equal pay or a harassment-free work environment right now, with no ramp-up. I’m certain that people of color would be able to deal with equal political representation and economic opportunity if they were made available today. So for whose benefit do we need to go so slowly? How can white men be our born leaders and at the same time so fragile that they cannot handle social progress?

What we have been told is great, thanks to the mediocre-white-man-industrial complex, just isn’t always that great. The image of the ideal white man—the bold and confident ones we end up idolizing, giving promotions to, electing to office—that image is often the epitome of mediocrity. And when entrusted with these positions of power, such men often perform as well as someone with mediocre skills would be expected to: we see the results in our floundering businesses and in our deadlocked government. Rather than risk seeming weak by admitting mistakes, white men double down on them. Rather than consider women or people

of color as equally valid candidates for power, white men repeat that a change in leadership is somehow “too risky” to entrust to groups that they have deliberately rendered “inexperienced.”

This discrepancy between our limited definition of greatness and what we’re left with comes in part from our insistence that our system is a meritocracy, when it clearly is not. There are all sorts of systems and institutional barriers that have worked for centuries to ensure that large segments of our society—regardless of talent, skill, or character—will never be allowed to rise out of poverty or powerlessness.

This country’s wealth was built on exploitation and violence, and those who worked hardest to build it were not empowered or enriched by its successes—they were enslaved people, migrant laborers, and domestic workers. Much of this country’s early infrastructure, for example, was built with slave labor, and then with grotesquely underpaid immigrant labor and prison labor. Many of our business and political leaders were freed to dedicate their time and energy to their professional success by the unpaid labor of wives and mothers and the underpaid labor of nannies and housekeepers.

Those who profited off that labor did little more than be born with a whip in their hand. But nevertheless we crafted a story of greatness around them. We say that they earned greatness, and that if we emulate them, these cruel and powerful white men, we will one day rise to where they stand.

When I say “we,” I don’t mean me. I am a Black woman. True, I have been told time and time again that my best chance of success is to emulate the preferred traits of white maleness as much as possible. Still, mine is not the image of the great leaders in our history books, nor that of the heroes in our stories. For someone like me to expect any greatness without having exceptional talent and luck was, at best, foolish and, at worst, dangerous. This is not my birthright.

There has always been a nagging discrepancy between the promise and the reality of white maleness. White men have often had the sneaking suspicion that the American dream is a fiction. At the same time, white men have always feared the potential of losing that one great superiority—the better than. If all you have is better than—better than women, better than people of color, no more and no less than that—why would you willingly give up the one prize you never had to earn?

Mediocre

Mediocre