- Home

- Ijeoma Oluo

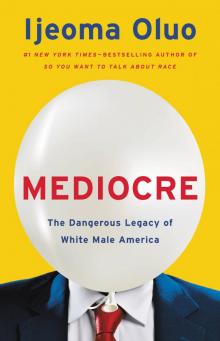

Mediocre Page 4

Mediocre Read online

Page 4

Cody would also come to regret the massacre of buffalo that had given him his stage name. While the great buffalo hunt featuring live bison would always be a prominent part of Cody’s show, he began to speak out against the buffalo hunting that he had popularized. Perhaps one of the most brutal of white male privileges is the opportunity to live long enough to regret the carnage you have brought upon others.

While I had, like many people, heard the name Buffalo Bill, he was not a featured hero in 1980s Seattle, as he has been in places like Wyoming or Colorado. About a decade ago, on a business trip to Cody, Wyoming (named after William Cody, who is considered one of the city’s founders), I happened upon the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. I knew very little about Buffalo Bill, but the five-museum complex seemed to take up an entire city block, and I had a few hours to kill before my flight back home. I decided to go inside.

Greeting me at the entrance of the Buffalo Bill museum was a stagecoach filled with memorabilia. There were countless artifacts from the Wild West show: Annie Oakley’s stage costume, the weapons of Native warriors, even a full-size replica of Cody’s personal show tent. I was both dazzled by and uncomfortable with the elaborate spectacle on display in these exhibits. I cringed looking at pictures of the “Zulu warriors” and read about how Cody was apparently very “forward thinking” on race and gender in his time—being a white man who was not afraid to pay the women and people of color who performed in his show (never mind that he paid them less than the white men). The magic just… wasn’t there for me. But then again, I’m pretty sure that I—as a liberal Black Seattleite who has no dreams of riding horses, shooting guns, or performing any acts of physical bravery or adventure at any time in my life—was not the target audience for this exhibit.

At the end of my time in the museum I almost passed by a display that was not nearly as flashy as the others. On a wall set slightly apart from the rest of the exhibits hung a set of black-and-white photographs. I took a closer look at one of the photos and I saw skulls. Thousands and thousands of buffalo skulls. Buffalo skulls piled dozens of feet high. White men proudly standing on mountains of buffalo carcasses. It was a series of photos acknowledging the massacre of buffalo by white hunters. Surrounding the photos were quotes from Native people lamenting the devastation as their beloved buffalo were hunted nearly to extinction.

Buffalo were a primary food source, but they were more than just food to the Plains Indians. The entirety of the buffalo was integral to their way of life. Bones were used for knives, skin was used for clothing and shelter, dried dung was used as fuel, sinew was used for bowstrings, horns and hooves were used as cups. And the connection to buffalo was not just physical; it was also spiritual. The Lakota view their nation as a sister nation to the Buffalo nation. Oglala Sioux leader Red Cloud tried to explain the importance of the buffalo to Roosevelt in 1903. “We told them that the buffalo must have their country and the Lakota must have the buffalo,” he recalled.22

There were an estimated thirty to sixty million buffalo in America at the beginning of the nineteenth century. By 1900, there were only around three hundred. Many of those few remaining buffalo were found in Cody’s Wild West show, where he staged his great buffalo hunts, proclaiming them the “last of the only known Native herd.” Crowds came from all over to gaze at the remaining few of the great beasts. Cody would later be praised for helping lead buffalo-conservation efforts by keeping American interest in the animals alive through his shows.23 The man who earned his name by killing buffalo is now honored for his commitment to their survival.

Other quirks of history abound in the Wild West show. When I first read about the scenes in which Native people were portrayed as naïve savages tricked into violence against white people by scheming Mormons, I was amused and a bit confused. The story sounded like a rather ridiculous—and oddly specific—tale of white-on-white crime. Why Mormons? Why were they attacking other white people? Why did they need to trick Natives into doing their dirty work for them? I chuckled to myself at how very outlandish the Wild West show must have been and wondered what sort of white people would have been entertained by such tales. But as I was researching the history of Mormon fundamentalism in the West, I came across an event that may well have been the basis for the Wild West stories—even if the reality was far too gruesome for any stage reproduction.

In 1857 the Baker-Fancher party, a group of white Christians, was making its way west from Arkansas in a wagon train. When they arrived in the Utah territory, they immediately began to clash with Mormon settlers, who had moved to the territory a few years earlier in hopes of establishing a homeland away from the religious persecution they had experienced back east. After years of being chased from state to state by angry and bigoted Christians, the Mormons were wary of outsiders and perhaps a little quick to the gun. This new land was to be their Zion, and they were required by God to protect it.

By the accounts that exist, the Baker-Fancher party felt that the land was theirs to use as well. They grazed their animals on pasture already claimed by Mormon families. They refilled their water from rivers that the Mormons believed were their own.

The Mormons had an uneasy relationship at best with the Paiute people. They occupied the Natives’ land, but they still convinced local Paiutes to help them scare off the Baker-Fancher party with the promise that they’d get to keep whatever livestock was left behind. I imagine that one colonizer was the same as the other to the Paiutes, and so some agreed to join the assault to at least earn some cattle out of the deal.

The Mormons, who darkened their faces with paint in an attempt to blend in with the Paiutes, launched their attack on September 7, 1857. It was supposed to be a quick ordeal—they would shoot a few interlopers who would then run away and leave the Mormons to the land they had rightfully stolen, and if anyone came asking, the entire thing could be blamed on the Paiutes. But the Baker-Fancher party did not run away, even though they were outnumbered. Fueled with the fervor of Manifest Destiny, just as the Mormons were filled with religious zeal, the Baker-Fancher party dug in for a fight. As the days dragged on, many of the Paiutes who had been promised a quick profit of cattle abandoned the battle, seeing that it was not worth the trouble.

Now, with fewer Natives to blame the attack on, the Mormons decided that the risk of being identified as the attackers was too high. The Mormons raised the white flag, calling for a cease-fire. The Baker-Fancher party laid down their weapons and came out of their shelters. They were then shot and hacked to death. James Lynch, a migrant traveling through Mountain Meadows a year after the massacre, documented the grizzly sight left behind: “Human skeletons, disjointed bones, ghastly skulls, and the hair of women were scattered in frightful profusion over a distance of two miles.”24 Every person over the age of six—120 innocent people in total—was brutally murdered in what is now known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The surviving children were kidnapped by Mormon families.

Only one of the attackers would face justice, a man named John Lee. Nephi Johnson, a Mormon who was at the Mountain Meadows Massacre, would testify that he saw Lee and “the Indians” murder the Baker-Fancher party. He testified that he himself hadn’t taken part in any killing and couldn’t recall seeing any other Mormons take part in the killing.25 Lee, in a long and very detailed confession, stated that “the Indians” who participated in the massacre were recruited by Nephi Johnson himself, and that they, Lee, and many other Mormon men had massacred the Baker-Fancher party on direct order of Mormon leaders who told them to “decoy the emigrants from their position, and kill all of them that could talk.”26

In 1877, twenty years after the massacre, John Lee was found guilty and shot by a firing squad. Despite his testimony of innocence, Nephi Johnson would be forever haunted by what happened on Mountain Meadows. On his deathbed, Johnson asked a young writer to hear his confession. But when she arrived, all he could do was scream, “Blood, blood, blood” over and over.27

In the story of the Mountain Meadow

s Massacre lies the tale of the battle for the West. White men battling other white men for land that was never theirs, leaving nothing but destruction in their wake. This pattern of entitlement and destruction would repeat itself in future generations all across the West, and would grab headlines in 2016 when two brothers, Ammon and Ryan Bundy, walked into the offices of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge, carrying rifles and thousands of rounds of ammunition, and decided to claim it for their own.

WHOSE AMERICA? THE BUNDY BROTHERS VS. THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Cliven Bundy is proud to trace his lineage back to Nephi Johnson. Johnson, who adopted Bundy’s grandfather John Jensen, is Cliven’s proof of his claim to the land around his ranch in Bunkerville, Utah. His adoptive great-grandfather came to the West in search of a uniquely American dream that at times placed Mormon settlers in direct conflict with the US government and often caused them to see themselves as different from “Americans,” the non-Mormon whites who had persecuted them and forced them West.

As the Mormon migrants claimed the territory of the Paiute people, their fierce antigovernment stance and religious devotion to protecting their claims to the land would merge with images of the ferociously independent Western cowboy. While Mormon settlers were mocked and villainized in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, you would be hard-pressed to find men in the present day who better fit the archetype of a Western cowboy than the Bundys and their rancher community.

Cliven Bundy had been raised in the independent American spirit, and he brought up his sons with the same insistence on being free from outside interference and from relying on the government. He also instilled in his sons the willingness to suffer—and make everyone else around them suffer—in order to maintain their independence.

Cliven’s son Ryan’s first political protest was in the third grade. The target of his protest was his own mother. Cliven had lost money on some cattle, and the family was having trouble making ends meet. To ease their burden, Cliven’s wife, Jane, signed up their five children for subsidized school lunch. Ryan, who had been taught by his father to never accept government handouts, refused to eat. In remembering the protest, Ryan stated that it reinforced the lesson that “we’re supposed to earn what we have and not to take from others.”28 Each day he sat quietly outside and refused to join his classmates at lunch. After three days, Ryan’s mother relented and began making lunches from home again.

Nothing says “American” like a boy making a woman struggle so that he can seem independent.

Cliven is not only against government handouts; he is also against government fees—especially from the federal government. He is a fierce opponent of federal grazing restrictions and fees and has counted the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) as an enemy for decades. He stopped paying the grazing fees for his cattle in the 1990s. His opposition to the BLM is both religious and personal. Cliven is part of a small sect of Mormons who believe that the Constitution was evidence of a divine plan to restore Zion in the United States. This is a warped patriotism that has designated them as the true interpreters of and heirs to American destiny. They believe that the Constitution invalidates any federal claim to land in the United States outside Washington, D.C. This appears to be a willful misreading of the Constitution, one that the Mormon church itself has rejected.29 Nevertheless, a sizeable minority of Western Mormons believe that the Constitution proves that the federal government has stolen land that is rightfully theirs, and that any grazing fees are just further theft. When you add in a religious duty to defend land that the Bundys and other Mormons believe is Zion, you get a fierce opposition to any other entity claiming authority over the land.

While the religious aspect of the Bundys’ opposition to the federal government might cause many to dismiss them as isolated zealots or weirdos, to do so would be a mistake. Antigovernment beliefs, and the specific belief that the federal government doesn’t have the right to dictate land use, are shared among many in the West—Mormon and non-Mormon. The Bundys themselves would show the rest of the country just how popular their opposition to the federal government is.

“When I went to visit the Bundys in 2015, I thought they were sort of an anomaly—an isolated family with radical beliefs that were launching this little regional war,” Betsy Gaines Quammen, a Western historian and conservationist who has written the book American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God, and Public Lands in the West, told me over the phone. “I’m really surprised at how explosive these ideas have become. It’s everywhere now.”30

The Bundys first rose to notoriety in 2014. After years of Cliven Bundy grazing his cattle on public lands without paying his grazing fees, and after many warnings, the federal government notified Cliven that it was going to round up his illegally grazing cattle and confiscate them.

The Bundy family rallied around Cliven as government trucks rolled into Bunkerville. When Cliven’s fifty-seven-year-old sister Margaret Houston tried to block one of the BLM’s vehicles, she was thrown to the ground by a BLM officer. The officer’s violent actions were caught on video, which went viral online.

Once the footage of a federal officer throwing a white woman to the ground on his way to confiscate a white man’s cattle reached other antigovernment groups, “patriot” groups, and militia groups, hundreds of people flocked to Bunkerville to support the Bundys. On April 12, 2014, the Bundy family led hundreds of armed supporters to the federal government’s holding pen for the Bundy cattle. They set up armed sniper positions and erected roadblocks. They were, according to Cliven, “ready to do battle.”31 BLM officers, seeing that they were on the edge of a very bloody fight, backed down—leaving the Bundys to reclaim their cattle. The Bundys celebrated their victory and immediately became heroes to whites who held antigovernment sentiments—individuals, militias, and white supremacist groups—throughout the West.

Antigovernment sentiment had thrived throughout the rural West since the time of Nephi Johnson. But the election of Barack Obama to the presidency caused an explosion in popularity of white nationalist and antigovernment groups in the region. People could mask their racist discomfort with a Black president behind a general distrust of the government and a “patriotic” desire to take America “back to its roots.” Cliven himself may believe that he is purely motivated by faith, his desire for independence, and his dedication to a misguided interpretation of the US Constitution, but it appears to be very hard for him to hide the racism that informs his beliefs.

In describing his beliefs to a New York Times reporter, Cliven went on a long racist tirade, opening with, “I want to tell you one more thing I know about the Negro,” which is never a good start. He dug up the common racist tropes about Blacks with nothing better to do than crowd welfare offices. “They abort their young children, they put their young men in jail, because they never learned how to pick cotton,” he ranted. In case anyone might have been wondering if they heard Cliven right and he was as racist as he sounds, he added, “I’ve often wondered, are they better off as slaves, picking cotton and having a family life and doing things, or are they better off under government subsidy? They didn’t get no more freedom. They got less freedom.”32

Anyway, the Bundys and the rest of the white, antigovernment sector of the West celebrated Cliven’s victory over the feds—a victory so decisive, they were downright cocky about it. After the feds abandoned their posts to deescalate the confrontation, Cliven demanded that local law enforcement turn over the BLM officers’ weapons to them.33 He felt confident that the feds had been scared away for a while. “They don’t have the guts enough to try to start that again for a few years,” he said. And he was right. It would be two years before Cliven would face any consequences for his actions.

But Cliven’s sons Ryan and Ammon were not content to wait for the feds to come back. Fueled by their victory over the BLM, the Bundy brothers were looking for the next opportunity to take on the federal government. They found it in the 2015 case of the Hammonds.

Like Cliven Bundy, Dwight Hammond had

a long-standing dispute with the BLM, mainly over grazing access to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. The 188,000-acre Malheur refuge required grazing permits in order to take cattle over the protected land, and Hammond, whose property bordered the refuge, greatly resented the inconvenience. Not only did Hammond flagrantly disregard the need for a permit; he also regularly sent the refuge staff threatening letters promising to “pack a shotgun in his saddle and no one will challenge me!” as he took his cattle through the refuge. He even cut holes through the refuge fence to let his cattle through.34

The BLM put up with Hammond’s antics for the most part, sending him letters and fines but otherwise leaving him alone, until he and his son Steven started setting fires. The Hammonds claim that they were lighting small fires on their land as part of wildfire prevention, but that they lost control of them. The government maintains that the Hammonds were setting fires to cover up their illegal hunting on the refuge. Two fires that the Hammonds set spread beyond their property onto public land—which is extremely dangerous and potentially catastrophic in a region known for its hot and dry climate. The Hammonds were arrested and charged with arson. After they were found guilty, a sympathetic judge sentenced father and son to relatively short sentences of three months and one year, respectively. The US Justice Department appealed the short sentences, and the Hammonds were given new, five-year sentences by a different judge.35

The Bundys and many in the ranching and antigovernment community were outraged at the perceived injustice of the Hammonds’ sentences. Ammon and Ryan Bundy felt called to take their battle with the federal government to Harney County in Oregon in support of the Hammonds.

Mediocre

Mediocre